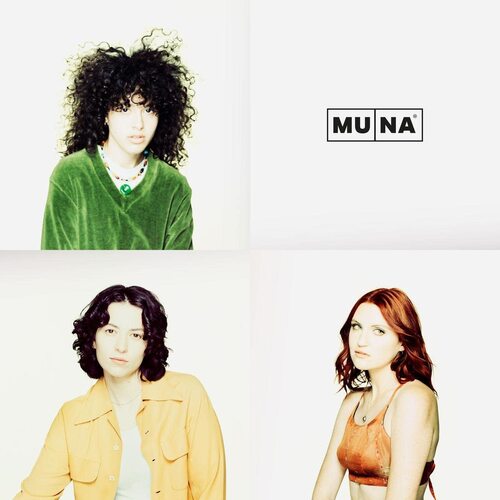

Muna is magic. What other band could have stamped the forsaken year of 2021 with spangles and pom-poms - made you sing (and maybe even believe) that "Life's so fun, life's so fun," during what may well have been the most uneasy stretch of your life? "Silk Chiffon," Muna's instant-classic cult smash, featuring the band's new label head Phoebe Bridgers, hit the gray skies of the pandemic's year-and-a-half mark like a double rainbow. Pitchfork called it a "swirl of stomach butterflies," NPR a "queerworm," Rolling Stone "one of the year's sweetest melodies, radiating the kind of pure pop bliss so many bands go for but almost never get this right." For Naomi McPherson, Muna's guitarist and producer, it was a "song for kids to have their first gay kiss to." And several thousand unhinged Twitter and TikTok memes bloomed. Katie Gavin, Muna's lead singer and songwriter, wrote "Silk Chiffon" right after finishing the band's 2019 album, Saves the World. That was an LP whose lead single began "So I heard the bad news/ Nobody likes me and I'm gonna die alone in my bedroom/ Looking at strangers on my telephone," and which ended with a hypnotic, self-searching confession about failure and consolation. Since the beginning of their career, Muna has embraced pain as a bedrock of longing, a center of radical truth, a part of growing up, and an inherent factor of marginalized experience - the band's members belong to queer and minority communities, and play for these fellow-travelers above all. But in "Silk Chiffon," there was just longing, and it was blissfully requited at that. "It's kind of a smooth-brain song," Gavin says. "Saves the World was therapy on a record, and I was starting to see changes in my life, more moments of joy. It's a big deal that someone like me could write that smooth!" What makes the confetti-gun refrain of "Silk Chiffon" so potent, though, is the underlying sense that the band understands exactly what has to be suppressed, or reckoned with, in order to sing it. "We are three of the most depressed people you could ever come into contact with, depending on the day," McPherson said, with a smile. Gavin, McPherson, and Josette Maskin, Muna's guitarist, are coming up on ten years of friendship. They began making music together in college, at USC, and released an early hit in the 2017 single "I Know a Place," a pent-up invocation of LGBTQ sanctuary and transcendence. Now in their late twenties, the trio has become something more like family. They spent much of the early pandemic as a pod, showing up for each other and for Muna - a project that at this point feels bigger than them - even when they weren't sure about anything regarding the future. They'd been dropped by RCA, and there was little in terms of income, no adrenaline to work off of, no live shows with audiences reminding them of the succor their songs provide. They asked each other: Is this career even feasible in this new reality? Can we find a way to be self-motivated, to be fulfilled intrinsically? For months, they surrendered to this confusion, to the reality of being humbled by change. "You have to let things fall apart," Gavin said. "And it was only possible because of this tremendous trust. I have so few relationships in my life where I have the kind of trust that I do with Naomi and Jo - where I can trust that there's a higher purpose, that we can work through all the boundaries and compromises and mess that comes with long-term relationships, and then return to form." Muna, the band's self-titled third album, is more than a return. The band's period of uncertainty and open questioning burned everything away, leaving a feat of an album - the forceful, deliberate, dimensional output of a band who has nothing to prove to anyone except themselves. The synth on "What I Want" scintillates like a Robyn dance-floor anthem; "Anything But Me," galloping in 12/8, gives off Shania Twain in eighties neon; "Kind of Girl," with it's soaring, plaintive The Chicks chorus, begs to be sung at max volume with your best friends. Muna is working the source code of pop that pulls at your heartstrings; the album is full of longing and revelation and hard-won freedom. They'd made their first album themselves, with free plugins, in a home studio; they'd made the second one in proper sessions with co-producers, thinking they ought to professionalize. With Muna, they did it all by themselves again, with newfound creative assurance and technical ability - in terms of McPherson and Maskin's arrangements and production as well as Gavin's songwriting, which is as propulsive as ever, but here opens up into new moments of perspective and grace. "What ultimately keeps us together," Maskin said, "is knowing that someone's going to hear each one of these songs and use it to make a change they need in their life. That people are going to feel a kind of catharsis, even if it's a catharsis that I might never have known myself, because I'm fucked up." McPherson added, "I hope this album helps people connect to each other the way that we, in Muna, have learned to connect to each other." And that's what Muna does, in the end: it carves out a space in the middle of whatever existential muck you're doing the everyday dog-paddle through and transports you, suddenly - you who've come to music looking for an answer you can't find anywhere else - into a room where everything is possible, where the disco ball's never stopped throwing sparkles on the walls, where you can sweat and cry and lie down on the floor and make out with whoever, where vulnerability in the presence of those who love you can make you feel momentarily bulletproof and self-consciousness only sharpens the swell of joy.

Release date:

June 24, 2022

Label:

Install our app to receive notifications when new upcoming releases are added.

Recommended equipment and accessories

-

Pro-Ject Phono Box DC Pre-Amp

Compact, high-performance phono preamplifier for both MM and MC cartridges, delivering a clean, detailed signal with minimal noise.

-

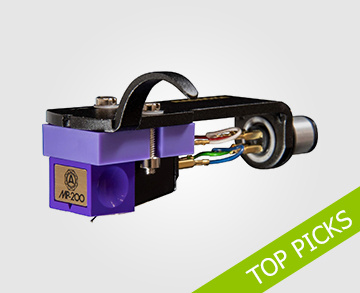

Cartridges - Top Picks

A selection of turnatble cartridges that provide great performance and sound quality

-

Ortofon 2M Blue Premounted

Mounted on the SH-4 Black Headshell, this setup delivers exceptional clarity, dynamic range, and accurate sound reproduction.

-

Vevor Ultrasonic Cleaner

Thoroughly clean and restore your vinyl records, removing dust, dirt, and grime from every groove without damaging the surface

-

Technics SL-1500C Turntable

Features a direct-drive motor, a high-precision tonearm, and a premium MM cartridge, delivering exceptional sound quality

Featured Upcoming Vinyl

-

Beths Expert In A Dying Field ("Head In The Clouds" Blue Eco-Mix)

Carpark Records

April 3, 2026 -

Dru Hill Enter The Dru [2xLP]

Def Jam

February 20, 2026 -

Wesley Joseph Forever Ends Someday

Secretly Canadian

April 10, 2026 -

The Scratch Pull Like A Dog

Sony UK

March 20, 2026 -

The Black Crowes A Pound of Feathers

Silver Arrow Records

March 13, 2026 -

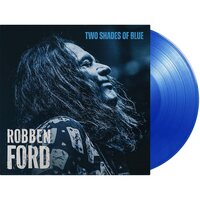

Robben Ford Two Shades of Blue

Provogue

March 27, 2026 -

Kishi Bashi Sonderlust (10th Anniversary; Gold/White) [2xLP]

Joyful Noise Records

February 27, 2026 -

Noah Kahan The Great Divide (American Rust) [2xLP]

Mercury/Republic Records

April 24, 2026 -

Buck Meek The Mirror (Clear)

4Ad

February 27, 2026 -

Mal Devisa Palimpsesa (Yellow) [2xLP]

Topshelf Records

March 13, 2026 -

Embrace Avalanche (Dark Blue Smoke)

Cooking Vinyl

June 12, 2026 -

Eaves Wilder Little Miss Sunshine (Orange/Yellow)

Secretly Canadian

April 17, 2026 -

Sunn O))) Sunn O [2xLP]

Sub Pop

April 3, 2026 -

Holly Humberstone Cruel World

Interscope/Geffen/A&M

April 10, 2026